The Greek prefix "meta", meaning 'after' or 'beyond', is often added to modern words to indicate that something is self-referential. For example, 'metahumour' is joking about jokes; 'metacognition' is the study and awareness of how we understand things (so, thinking about thinking). Metadata, then, is data about data: information that describes various aspects of a digital asset. Such assets might include photographs, documents, videos, web pages, etc, and metadata for those assets could include its title, date of creation, who created it, keywords, and any number of other details about that asset.

|

|

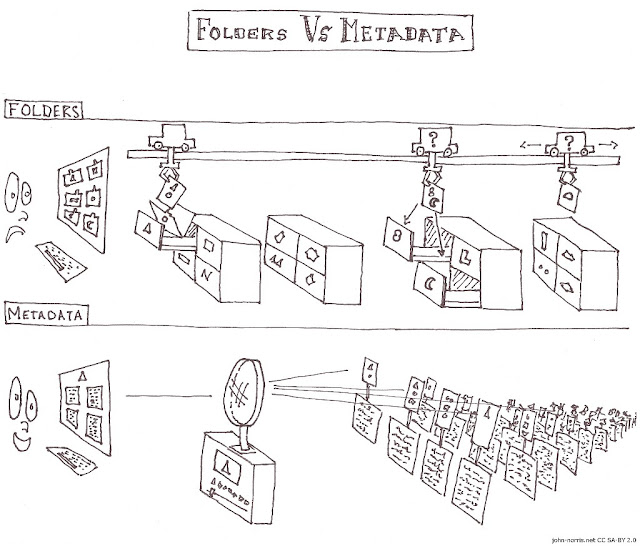

Folders Vs Metadata

by John Norris,

CC BY-SA 2.0 John Norris has provided an in-depth explanation of the ideas depicted in the cartoon on his blog. |

Metadata acts as a digital label and its key purpose is to enable efficient management, sorting and discovery of content. A self-referential example of metadata would be the labels associated with the article you are reading now: if you scroll down, just beneath the Further Reading section you'll see the word "Labels:" followed by some key words that relate to themes and topics represented in this article. Clicking or tapping on any of those words will take you to a list of all of the articles on this site that have been assigned that word as a label. In this context, 'labels', 'tags' and 'keywords' are all the same kind of metadata.

As large numbers of digital resources are created and stored they can quickly become unmanageable. Ensuring that each asset is tagged with relevant metadata plays a crucial role in ensuring that the time, effort and, in many cases, money that has gone into creating such resources is not wasted: good metadata enhances accessibility, improves search capabilities and facilitates the preservation and contextual understanding of digital resources, and all of this adds to its usefulness.

Exactly what metadata is required depends on the resources themselves and possible use cases and so it is not possible to provide a definitive list of metadata categories that works in all circumstances, but the following considerations may help you to decide what is required in your own context:

A useful metadata schema should contribute to all of the following:

Content organisation

Resource discovery

Contextual understanding

Collaboration and data sharing

Next steps

- A common place where digital assets produced by museums and galleries are stored but metadata is neglected is the organisation's website, so:

- Browse your organisation's website. What digital resources can you find? Is a metadata schema apparent (i.e., are resources and web pages visibly 'tagged' with appropriate key words)?

- Try using the search features of the website to find information and resources on themes that you are interested in. Is what you find relevant?

- Are any of the resources you find missing important keywords? Make a note of the URL and any keywords that you think should be attached.

- Explore websites and online resource collections for other organisations (e.g.: the Wellcome Collection). Think about the same things as in step #1 above.

- Go back to your organisation's website having explored others in step #2. What features of your website make it easier or more difficult to find and sort information effectively? Can you think of any improvements to suggest?

- Discuss your thoughts and findings with colleagues within your organisation, and/or with other museum educators.

Further Reading:

- From the Glossary: Digital Skills

- Elsewhere online: Metadata (Wikipedia) | How to Build a Metadata Plan (AIIM) | Introduction to Metadata (3rd Edition) (Getty)

Comments

Post a Comment